The Color of Love

November 6, 2014 § 1 Comment

I was digging around in my Just Like Family content files recently and came across a letter-to-the-editor from a 1997 Utne Reader. I had always meant to locate the article, “The Color of Love,” to which it referred, and finally, with some effort, I found it in the archived magazine collection in the dusty basement of the local university. The letter-to-the-editor states the following:

As a black woman, I am weary of reading these oh-so-tender stories of white families who “love” their black maids. I have never heard a little black girl say, “I want to be a maid when I grow up.” I suspect that, just as Daniel Stolar [the author of “The Color of Love”] has never seen the upstairs of Lillie’s home, he has never envisioned the “upstairs” of her ambitions. After her years of faithful service, did he and his parents ever ask Lillie what her dreams were, and how they could help make them come true? If their “love” for Lillie was contingent on her continuing to clean up after them, then I respectfully suggest that a more appropriate title for Stolar’s article would be “The Color of Money.”

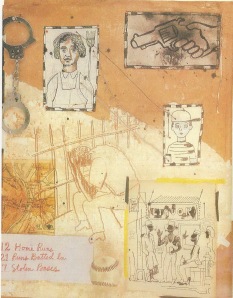

Lillie (no last name given) worked for Stolar’s family for 27 years, raising him as well as doing housework and cooking. When Stolar was 12, Lillie’s son James, an older playmate of Stolar’s, was imprisoned for murder—he drove the getaway car after his accomplice killed a white man in St. Louis’s Forest Park and was jailed for life. Stolar’s affluent and civic-minded family had led the effort to restore the majestic urban park, the second-largest in the country, which, for a period of time, was “surrounded by row upon row of dismal boarded-up tenements.” The kind of housing that Lillie lived in. The tall muscular James, who had tried out for the St. Louis Cardinals, was at once distant and attentive. He coached Stolar in baseball. James was his idol. In later years, Stolar questioned whether James’s coaching was nothing more than an extension of the servant-employer relationship his mother had with his parents. Although Stolar’s influential parents were able to convince the courts not put James on death row, he was later killed in prison by another inmate. After James’ death, Stolar was discomforted when Lillie would say that she had only one son now–him.

Lillie (no last name given) worked for Stolar’s family for 27 years, raising him as well as doing housework and cooking. When Stolar was 12, Lillie’s son James, an older playmate of Stolar’s, was imprisoned for murder—he drove the getaway car after his accomplice killed a white man in St. Louis’s Forest Park and was jailed for life. Stolar’s affluent and civic-minded family had led the effort to restore the majestic urban park, the second-largest in the country, which, for a period of time, was “surrounded by row upon row of dismal boarded-up tenements.” The kind of housing that Lillie lived in. The tall muscular James, who had tried out for the St. Louis Cardinals, was at once distant and attentive. He coached Stolar in baseball. James was his idol. In later years, Stolar questioned whether James’s coaching was nothing more than an extension of the servant-employer relationship his mother had with his parents. Although Stolar’s influential parents were able to convince the courts not put James on death row, he was later killed in prison by another inmate. After James’ death, Stolar was discomforted when Lillie would say that she had only one son now–him.

Since childhood, Stolar considered what to call Lillie—maid, housekeeper, nanny, even good-friend-of-the-family, or adopted aunt, or surrogate mother. His need to give title to Lillie arose from his “inability to explain her role in my life and my embarrassment about it. But these are not titles that clarify. In their very inadequacy, they point to an underlying cliché, colored perhaps with racist assumptions: Jewish white boy raised in a well-to-do inner-city enclave by professional parents with a black maid….”

Still, at 76 (her age in 1997 when the article was written) she came to work at his parents’ home two days a week. She continued to cook dinner, wash dishes and go on a weekly grocery-shopping trip. The family also used a professional maid service for what the parents called “the real cleaning.”

Stolar contemplates if he could be part of the murder instead of James. “No matter how I try, I can’t imagine arriving at the handball courts as James did that afternoon. It could never, ever have been me in the car with the black man who became a murderer that day. This is the real answer to the questions that troubled my 12-year-old mind. The reality of living 24 hours a day in a black man’s skin in north St. Louis is unimaginable to me. How could it be otherwise?”

Stolar visited Lillie often after she retired and states that after many visits he had never been upstairs in her house. The letter writer sees this as evidence that Lillie did not feel the intimacy toward him that he felt toward her. He says, “I’m still trying to figure out exactly what Lillie’s role has been in my life. Yes, I love her. Yes, I have depended on and confided in her. But have I really known her? Have we ever met on equal grounds?”

Stolar’s questions are, of course, rhetorical. He knows that he and Lillie could never meet on equal ground. Like his reflections on James, how could it be any other way? He was the son of affluent parents. She was one of many exploited black women in the middle of the 20th century caught up in someone else’s household, stereotyped in the figure of “Mammy.” At that time in the United States, Lillie was viewed as an inferior. She was there to cook and clean. And like many whites raised by African American women, Stolar felt guilt and shame, not knowing who his caretaker really was, what to call her or their relationship. The care-giving relationship would not have developed under any other conditions. Lillie and Stolar were as far apart as people could get even after a lifetime of connection. We can’t know how Lillie felt or what her dreams and aspirations were or whether her employers sought to help her reach some goal as the letter writer doubts. All we know is that she worked for Stolar’s family for 27 years and was in a relationship with them that was surely fraught with the confusions and sublimations characteristic of connections based on the inequalities of race and class.

I meant to tell you yesterday that I had read the letter (but not yet the article). It’s haunting — “no little girl dreams of growing up to be a maid” Thanks for this, as for all your posts. I learn a great deal every time.